Re-post: The Dunning-Kruger effect

We've all experienced situations where we've run into people who seemed unable to estimate their own (lack of) skills in a particular area. It might be as extreme as the Creationist who tries to explain science to the scientist, but it can also be people in your day to day life, who overestimates their own skills in one thing or another.

There are two explanations for this. One is the "above-average syndrome", the other is the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The "above-average syndrome" is, simply put, that the average person in a given field will believe themselves to be above average. In other words, more people believe themselves above average than really are. Obviously, only 50% can be above average, but there are perhaps 80% who believes they are.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is related to the above-average syndrome, but it's one explanation of why this syndrome exist (there can be other reasons). The effect is named after Justin Kruger and David Dunning who made a series of experiments, which results they published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in December 1999. The title of the article was Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments (.pdf), which to my mind is one of the greatest titles I've ever seen on an article.

I highly recommend downloading the article, and reading it. It's fairly straightforward, and you don't need any background in psychology to understand it.

Dunning and Kruger looked at the above-average effect, and formed the hypothesis that it takes skills to evaluate yourself. With that hypothesis in mind, they set out to make a number of experiments to either disprove it, or to support it. Since I'm writing about the effect now, you've probably already figured out that their experiments supported their hypothesis.

Their experiments were fairly straightforward:

- Ask people to do some tests.

- Get people to evaluate how well they did compared to others.

At later tests they also included the following:

- Show people how others did.

- Get people to re-evaluate their level compared to others.

First they put people through a number of tests in different areas, and afterward asked them to evaluate how well they would do compared to others based on how they perceived their skill level. The results can be seen in the following figure from the paper.

As can be clearly seen, while the trend line of the perceived skill level was correct, everyone who took the tests believed that they were in the 3rd quartile. In other words, while the people in the 1st quartile estimated themselves lower than the people in the 2nd quartile, they vastly overestimated their abilities compared to others (by some 50 percentage points).

As the study says, there are two potential sources for the this wrong estimate, which Dunning and Kruger tried to evaluate.

Finally, we wanted to introduce another objective criterion with which we could compare participants' perceptions. Because percentile ranking is by definition a comparative measure, the miscalibration we saw could have come from either of two sources. In the comparison, participants may have overestimated their own ability (our contention) or may have underestimated the skills of their peers.

The way they tested this, was by not only asking people to compare themselves with other people, but also by asking them to tell how many questions they thought they had answered correctly. If they were correct in the number of questions they had answered correctly, this would mean that they had underestimated the skills of their peers rather than overestimated their own skills. This was, unfortunately, not the case. It turned out that people were actually pretty good at estimating how many correct answers would place them in their position, but were not able to estimate how many answers they would answer correctly.

In other words, it was not a failure of estimating others, it was a failure of estimating themselves (this held true across all quartiles, but was most strikingly among the lowest quartile).

All in all, the test results pretty much supported the hypothesis which Dunning and Kruger had made, but while it demonstrated the inability of people to estimate themselves, it didn't really address whether people would have the skill-set to re-evaluate their ability.

This is also something Dunning and Kruger set out to test.

Participants. Four to six weeks after Phase 1 of Study 3 [a grammar test] was completed, we invited participants from the bottom- (n = 17) and top-quartile (n = 19) back to the laboratory in exchange for extra credit or $5. All agreed and participated.

Procedure. On arriving at the laboratory, participants received a packet of five tests that had been completed by other students in the first phase of Study 3. The tests reflected the range of performances that their peers had achieved in the study (i.e., they had the same mean and standard deviation), a fact we shared with participants. We then asked participants to grade each test by indicating the number of questions they thought each of the five test-takers had answered correctly.

After this, participants were shown their own test again and were asked to re-rate their ability and performance on the test relative to their peers, using the same percentile scales as before. They also re-estimated the number of test questions they had answered correctly.

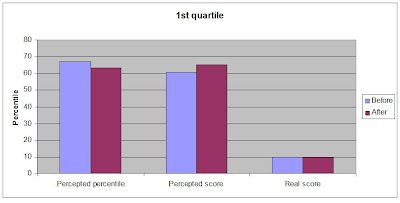

The results were very interesting, as can be seen in the two figures I'e made based upon the numbers from the article.

As the figures plainly show, the people in the highest quartile could use the information they gained to adjust their evaluation in the correct direction, though they were still too low. The people in the lowest quartile on the other hand, were unable to properly estimate their own effort, and actually misjudged their score even more afterward.

All in all, the tests supported Dunning and Kruger's hypothesis, and it gives us a better understanding of why people some times are so bad at judging their own skill level.

Having said all that, I should probably mention that later researchers disputes some of the conclusions made by Dunning and Kruger. In Skilled or Unskilled, but Still Unaware of It: How Perceptions Difficulty Drive Miscalibration in Relative Comparisons (.pdf) Burson et al. argues that it's not just unskilled people who can have a hard time evaluating their own skill level.

People are inaccurate judges of how their abilities compare to others’. J. Kruger and D. Dunning (1999, 2002) argued that unskilled performers in particular lack metacognitive insight about their relative performance and disproportionately account for better-than-average effects. The unskilled overestimate their actual percentile of performance, whereas skilled performers more accurately predict theirs.

However, not all tasks show this bias. In a series of 12 tasks across 3 studies, the authors show that on moderately difficult tasks, best and worst performers differ very little in accuracy, and on more difficult tasks, best performers are less accurate than worst performers in their judgments. This pattern suggests that judges at all skill levels are subject to similar degrees of error. The authors propose that a noise-plus-bias model of judgment is sufficient to explain the relation between skill level and accuracy of judgments of relative standing.

In the Burson et al. study, the best quartile underestimated themselves when dealing with hard tasks as the worst quartile overestimated themselves when dealing with easy tasks.

This doesn't necessarily invalidates the Dunning-Kruger effect, but it does tell us that we can't rely on people to correctly evaluate themselves, no matter their skill level.

Labels: Dunning-Kriger effect, psychology, re-post